| Having trouble reading this newsletter? Visit https://ymlp.com/archive_gesgjgm.php | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

August 1, 2025 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Newsletter for the

Offshore Residents of Pittwater, Australia - Volume 26,

Issue 1228

We acknowledge and pay our

respects to the Traditional Custodians of Pittwater,

as well as our Indigenous readers

|

||||||||||||||||||

Contents:Are We Idiots?The stories we tell ourselvesRoy Baker

It’s often said that a

community is built on the stories it tells about

itself. That’s probably because it’s true.

My village in England was known as the place where they put a pig on a wall so that it could watch a band go by. No one knows where this story comes from. Was my village once home to a music-loving pig? Was the local band so bad that it would take whatever audience it could get? Or do I come from a village of idiots? The last explanation is surely closest to the truth. It’s not that the people I grew up with were stupid, rather that Gornal, a Black Country community, is well used to the massive condescension heaped on the industrial working class. Why wouldn’t people mock us with made-up stories? Gornal was long considered a cultural backwater, to the extent that the Norman invasion seemed to pass us by—as a child I was aware that my community spoke a Saxonic dialect barely discernible as modern English. We were, to put it mildly, a bit backward and a little bit odd.

One story is that there

was grass growing on a town wall, so the villagers

hoisted a cow up onto the wall so that it could

graze there. Sadly, the rope was tied around the

cow’s neck, so the poor bovine was effectively

lynched.

The similarity between the stories is striking, but almost certainly coincidental. No one knows the origin of the Gornal story, but the Schildbürger stories first appeared in published form in 1597. This was in the later stages of the Reformation, and one theory is that the Catholic Church created—or at least weaponised—these stories to mock Lutheran communities in Saxony. If so, the stories reveal, respectively, religious friction and class tension. There are other differences between the stories, not least that no harm came to the Gornal pig, except that it presumably ended up on a plate. But what interests me is how modern communities have embraced these stories. In my childhood, the people of Gornal were very proud of their pig on the wall—to the extent that a local pub came to bear the name.

Stories of communities of fools are not uncommon. Besides Gornal and the Schildbürger we find the ‘Wise Men’ of Gotham (England), of Chelm (Poland), of Hoshiarpur (Punjab), and of Mornac (France). Do we residents of Pittwater fulfil a similar role in Sydney? After all, choosing to live in a community accessible only by boat is not everyone’s definition of sanity. If we are the butts of ribaldry, let us follow the examples of Gornal and Schildau and embrace our fate. In doing so, we quietly triumph over adversity, a hallmark of off-shore living. After all, isn’t self-effacement among the most endearing of human qualities? We can’t choose the stories they tell about us, but we can choose the ones we tell. ‘A people are as healthy and confident as the stories they tell themselves,’ said Nigerian poet and novelist Ben Okri. As offshore residents, we might not pride ourselves on having chosen conveniently sited homes. But let us honour what we have, and endeavour to tell ourselves stories that replace rancour with reconciliation, division with dialogue, and acrimony with acceptance. Scotland Island's Emergency Water SupplyA history

Scotland Island’s

emergency water system consists of over 3 km of

polyethylene pipe, about 140 standpipes, countless

valves and connectors, a sophisticated water pump

system, and a custom-automated booking system. How did

it get here? Who paid for it? Who maintains it? What

do they mean by non-potable? And if Sydney Water

charges $2.67 per kilolitre, why do we pay $6.43?

In this article, the first of two, SIRA’s accountant Boyd Attwell examines the system’s history. In next month’s PON he’ll tell us more about the current financials. Celebrating nearly 50 years of emergency water on Scotland IslandBoyd Attwell It may come as a surprise to newcomers to the island, and perhaps to some older residents, that the set of black plastic tubes you often step (or drive) over came into being by a rather complicated set of events, as well as the work of many island residents over a period of over 40 years.In 1977 Warringah Shire Council installed a small diameter submarine pipeline from Church Point to a modest steel tank on Richard Road. The water was expressly for the purpose of fighting fires and 'washing down fire fighting equipment'. For the 20 years that followed, there were modifications to the supply line and storage tanks and there was an unofficial shift of the service to supplying households that had run out of rainwater or were tired of lugging water containers home: it was not uncommon in the early days to see ferry passengers with 20 litre jerry cans of drinking water at their feet. Unfortunately, the unauthorised connections to the system were not always well thought through, risking contamination of the system.

For its own reasons,

perhaps relating to health risks and a wish not to be

exposed to legal action, Pittwater Council declared that

its single supply line of water to the island would

cease to operate on 30 June 2002.

SIRA’s 2002 submission to

Council included the sobering statement; 'houses would

be rendered uninhabitable, with its potentially

catastrophic financial impact on the families concerned

and consequent diminution of house and land values'.

Meanwhile, Sydney Water

actively sought to withdraw itself from the situation.

They chose not to recognise SIRA or any island residents

as customers, as if we were outside their geographic

responsibility, even though the island was a mere 500m

from a Sydney Water main supply valve.

What was the residents’

association to do? Well, one thing SIRA knows how to do

well is meet. It met, lobbied, wrote submissions, made

phone calls, and created endless documents, spreadsheets

and proposals.

SIRA and all Scotland

Island residents were victorious. An arrangement was

struck that allowed Sydney Water to supply the local

authority, for the local authority to supply SIRA, and

for SIRA to supply island residents. Complicated, yes,

but Sydney Water would not allow any other formula.

Council stipulated that SIRA should charge water buyers

an amount that covered reasonable costs, including for

maintenance of its water supply network, plus a 20%

service commission. The initial price to residents in

2002 was $4 per kL (kilolitre), plus a $10 booking fee.

With no history or expertise in selling water, these

prices were simply those recommended by senior managers

within Pittwater Council.

How did SIRA use

the money it charged customers?

Back in 2002, when SIRA was

charging customers $4 per kL of water, SIRA paid Council

94 cents out of that $4 for the water. SIRA then paid

water monitors 80 cents out of the $4, plus the full

booking fee charged to customers. That left SIRA with

$2.26 per kL it sold.

Remember that SIRA faced

set-up costs, as well as ongoing expenses arising from

maintaining the lines and clearing the vegetation that

grew over them. Fortunately there was an enormous amount

of time volunteered by many to initiate the system. An

additional plus was that some government grants were

secured. Then, people like Cass Gye spent uncountable

hours on maintenance.

Perhaps the initial

pricing of $4 per kL was a little over the mark, or

perhaps it was simply the input of so many unpaid hours

of work, but the early years of SIRA’s trade in water

proved profitable. Over the ensuing decade it

accumulated approximately $90,000 in reserves. It was

understood at the outset that SIRA would be responsible

for replacing the water infrastructure when the time

came, so the reserve was set aside for that purpose.

Note that SIRA chose not to

increase its prices with inflation. The price SIRA

charged for water was frozen at $4 per kL until July

2016, even though during the same period other costs

went up by 42%, according to the CPI. But by 2016 it had

become clear that the water that had previously been

sold at a profit was now being sold at a loss, and that

that was unsustainable, especially if SIRA was to retain

the reserve to replace the water line at the end of its

useful life.

In 2016 the price per kL

was increased to $5 and since then there has been a

practice of increasing the water price and the booking

fee annually by CPI.

The initial outlays to

establish these assets were mainly via state and local

government funding, plus the large volunteer effort

already mentioned. But buyers of emergency water

effectively paid, and continue to pay, for the

maintenance of the system.

In 2019 the organisation

received funding of $39,800 to create a customised

automated water booking system. In 2021 a further

$30,000 in funding was secured to acquire a water pump,

so that good pressure was available to all properties at

all times.

Who actually carries out the maintenance? SIRA! And SIRA has many

people to thank for their tireless efforts over the

years. The current water manager is John Courmadias, and

the water monitor is Rowena Dubberley. Steve Valenti

does a lot of the maintenance and line clearing. Thanks

go also to the Men’s Shed for their work helping to

upgrade the standpipes. Marie Minslow serves as the

Emergency Water team leader on the SIRA committee.

Finally, what do they mean by non-potable? Its not a snooker term. On

the mainland the water that comes out of the tap is

considered by Sydney Water to be ‘potable’, ie suitable

for drinking. Sydney Water has no direct relationship

with SIRA or the residents of Scotland Island. They make

no warranty of the water that has left their assets and

been delivered through polyethylene pipes. They consider

it ‘non-potable’.

In the next PON I shall answer some other questions you might have, such as how SIRA accounts for the price it currently charges. I'll talk about whether SIRA makes a profit or loss on sales, and what most residents think of the service. To find out more about the island's emergency water system, click here. Island Fire Brigade AGMAnother busy year of active service

Scotland Island’s fire brigade

held its AGM on 6 July—an opportunity to celebrate and

acknowledge the women and men of our community who

give so generously of their time and effort. The

meeting was attended by representatives of RFS

district office, who are themselves volunteers and

kindly gave up their Sunday mornings to help our

brigade.

The meeting began by

welcoming as full members those who have completed

their probationary period: Jeremy Sala, Maria Burke,

Emma Ives, Ian Hancock, Nicholas Kelly, Chris Garland,

Chris Canty, Tim Pines, Jamie Ives and Andrew Shields.

Also welcomed were five new recruits, drawn from across the generations—showing that any islander can contribute: Emile Attewell, Jordon Robertson-Towner, John Courmadias, Robert Fox and Robyn Iredale. Indeed, we really do need everyone’s support. Captain Peter Lalor reported a total of 38 emergency incidents attended during the last year—almost one per week. Many were medical call-outs, which draw on the care and expertise of our community first responders, led by Ian White. Alongside emergency responses, the brigade completed hazard reduction work in Catherine and Elizabeth Parks, ran regular training sessions (including joint drills with mainland brigades), and held a range of community events, including the annual Santa Run and Easter Egg Hunt.

Most of the executive committee was re-elected, but two have stepped down. Lara Hasell retired after 10 years as treasurer, and her diligence was warmly acknowledged. Vanessa Barry also resigned as secretary and is similarly thanked for her contribution. In their place, we welcome two new committee members. Robyn Iredale—former SIRA president—continues her sterling community service as our new secretary, having already acted in the role in recent months. Robert Fox is our new treasurer, and we’re grateful to him for his time and accountancy expertise. Thanks also to David Sutherland, who retired after many years as our auditor. Jennette Davidson has kindly agreed to take on that important role. In other good news, Emmie Collins and Janet Lambie agreed to share the role of social secretary—raising hopes that our long fire shed dinner fast may soon be over. Three awards were announced. Jamie Ives is our Member of the Year, Cat Heller is CFU Member of the Year, and Ross Hardy CFR Member of Year. Their dedication is greatly appreciated, as is that of all our members. On a personal note, I thank Steve Yorke for covering for the brigade’s recalcitrant president as I once again winter in Europe, and Peter Lalor for sorting out the paperwork after the AGM. He, as always, has gone above and beyond as captain. Finally, the meeting resolved to retain the annual subscription at $20 per year (life members exempt). Payment for 2025-26 is now due: Account name:

Scotland Island Rural Fire Brigade

BSB: 082 294

Account: 509351401

Roy Baker President Island CaféCatherine Park, Scotland IslandSunday 24 August, 10 am - 12 noon International Folk DancingScotland Island Community HallSaturday 30 August, 7 - 9 pm To help defray

expenses, the Recreation Club ask for $5 per person

per attendance.

Black Tie GalaWaterfront Café, Church PointSaturday 13 September, 6 pm onwards For SaleHand-knitted cotton face washers & dishcloths

Missed out on a previous newsletter? Past newsletters,

beginning May 2000, can be found at https://ymlp.com/archive_gesgjgm.php.

To ContributeIf you would like to contribute to this newsletter, please send an e-mail to the editor (editor@scotlandisland.org.au).Subscription InformationTo subscribe or unsubscribe, go to: http://www.scotlandisland.org.au/signup.

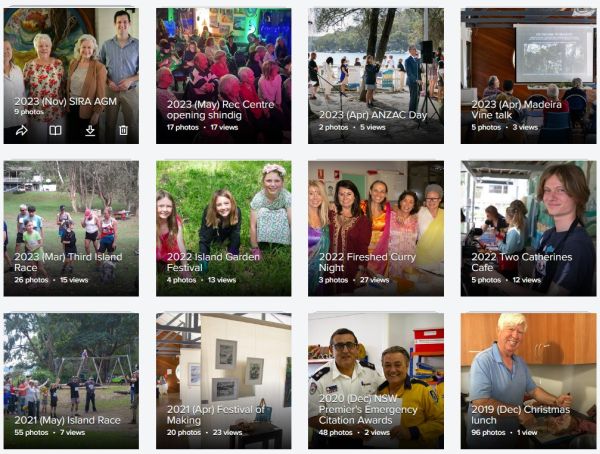

Scotland Island Community CalendarFor further information on island events, click hereThe Online Local Contacts GuideClick here to loadSIRA Photo Archive |

||||||||||||||||||

|