| Having trouble reading this newsletter? Visit https://ymlp.com/archive_gesgjgm.php | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

October 1, 2023 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Newsletter for the

Offshore Residents of Pittwater, Australia - Volume 24,

Issue 1199

We acknowledge and pay our

respects to the Traditional Custodians of

Pittwater, as well as our Indigenous readers

|

|||||||||||||||||

Contents:Who Owned Scotland Island?Tracing the island's title from 1810 to 1892Roy Baker

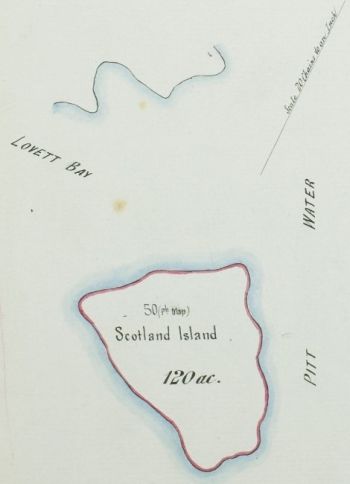

Andrew Thompson was granted Scotland Island in January 1810. He died later the same year. So who owned the island for the rest of Pittwater’s first century under colonisation? The best answer is that we may never know. Uncertainty remains even if we close our minds to Indigenous claims to land, something we should never do. But if we are to make headway in piecing together Scotland Island history then we need, for current purposes, to focus exclusively on those property rights and interests recognised by the conquerors’ laws.

Compare that with the system that existed in the early years of colonisation. The traditional way to establish ownership of land is through a chain of title. This involves documenting the sequence of transfers of ownership back to the year dot. What constitutes the year dot varies, but in the case of New South Wales a good starting point is the original grant of land from the Crown. In the case of Scotland Island that was 1810. In some situations establishing a chain of title is straightforward. But what if a link in the chain is open to challenge? Perhaps someone once forged a document, or papers got lost or destroyed. That’s when things get complicated. Following Thompson’s untimely death in 1810 his executors faced a daunting task. First they had to liquidate Thompson’s vast estate. Then they had to divide the proceeds among numerous beneficiaries, including Thompson’s estranged family in England. To complicate matters, Thompson’s brother vacillated so long over whether to accept an inheritance that the estate was not settled until 1825, 15 years after Thompson’s death.

Enter now another questionable character: John Dickson. Also from Scotland, Dickson arrived in Sydney as a free settler in 1813. He was an engineer, and brought to Australia its first steam engine, which he set up in what is now Darling Harbour. ‘A great Acquisition to the Colony’ was how Governor Macquarie described Dickson, and he swiftly became one of NSW’s great landowners. Dickson claimed ownership of Scotland Island in 1833, the year of his downfall. It began with him being sued for repayment of a debt. In his defence Dickson sought to rely on a forged document. He lost the case and then faced criminal prosecution for forgery. Rather than face trial, Dickson absconded to England while on bail and died in London 10 years later. Two of Dickson’s sons followed their father to England, but they appointed Edwin Daintrey, a Sydney lawyer, to oversee the family estate, which they said included Scotland Island. In 1855 Daintrey leased the island to Joseph Benns, a Belgian mariner, and to Charles Jenkins, a farmer. For seven years Jenkins and Benns paid rent of £10 pa until, for reasons unknown, they concluded that the Dicksons didn’t own the island. They stopped paying and in 1861 Daintrey threatened them with eviction. Remember that Torrens title was yet to be introduced to New South Wales. Working out who owned the island 36 years after the settlement of Thompson’s estate would have been a herculean task. Did it belong to the Dicksons, the Murrays, or someone else altogether? Fortunately for Jenkins and Benns, an ancient principle of English common law came to their aid.

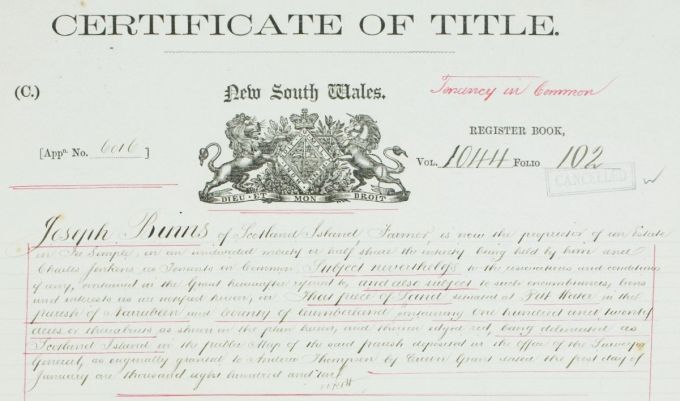

Assuming that the Dicksons owned Scotland Island, that would mean that while Jenkins and Benns were paying rent they were occupying the island with the owners’ consent. For that reason adverse possession couldn’t arise. But once Jenkins and Benns were given notice to quit then they were clearly occupying the island as squatters and the twelve-year countdown to ownership could begin. Jenkins and Benns’ first attempt to attain title failed. But in 1890 they tried again. To support their case they argued that they had occupied the island since the 1850s. In that time they had constructed a path around the island, leading from their residence (believed to be near Tennis wharf) and cut into the side of the hill near the water. They had also cultivated around 10% of the island, while livestock grazed on the rest. The Oliver family, who owned much of the western foreshore, lent their testimony in support of the claim. This time the Jenkins and Benns succeeded. Certificates of title were granted to them on 8 February 1892, meaning that, for the first time in almost 80 years, the island had incontrovertible owners. And thus was the path laid for the island’s eventual development for housing. This article draws on a number of primary and secondary sources, most notably a paper by George and Shelagh Champion. Thanks go to Craig Burton for his continuing encouragement to pursue this research.  How Do We Stack Up?Comparing Scotland Island with the mainlandRoy Baker

The release of the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest census data provides us with an opportunity to see how Scotland Island compares with the rest of Australia. I provide my analysis below. Apologies to readers from the western foreshores, but the way the ABS presents its figures makes it difficult to run this exercise in terms of the offshore community as a whole. The 2021 census recorded that 711 people were ‘usually resident’ on Scotland Island on the night of Tuesday, 10 August 2021. But the island’s population is partly seasonal: around 23% of the 358 private dwellings on the island were classed as ‘unoccupied’ that winter’s night. Given the number of weekender and holiday homes, it’s likely that the island’s summer population approaches one thousand. In terms of household composition, Scotland Island is not particularly different from any other suburb. Out of the 260 island dwellings that were occupied in winter 2021, 37% provided housing for a couple with one or more children, 30% contained couples with no children, 22% were occupied by an adult living alone and 10% housed a single parent with one or more children. The average number of people per household was 2.5. These figures are roughly on par with the rest of Australia. But our gender mix is not quite the same as that for Australia generally. Of the 711 people living on the island in August 2016, 52% were male: the figure for the nation as a whole is 49%.

Given that we have slightly more children than usual, and fewer of us are elderly, what accounts for the older median age? The island has a dearth of young adults. Barely 13% of islanders were in their 20s or 30s, whereas 28% of Australian residents are aged between 20 and 39. In contrast, the island had a whopping 34% of its population in their 40s or 50s, as opposed to 25% across the nation. Being older, the typical islander has had longer to marry (50% versus 47%), but also more time to separate or divorce: 17%, against Australia’s 12%. Thus far we islanders don’t seem so different from other Australians. We are just more middle-aged. But we start to see bigger differences when we look at our ethnic diversity. In some respects our suburb is much the same as many others. For instance, around two thirds of islanders were born in Australia, broadly similar to Australia as a whole. What is more, the chances of meeting an islander with both parents born in Australia are not so different from those of finding someone with similar parentage in another suburb: 37% for the island, 46% for elsewhere. The difference lies more in where the island’s 37% migrant population comes from. In terms of countries where English is widely spoken, New Zealanders are more common on the island than elsewhere in the country, as are Canadians and Americans. As for countries of origin where English is not an official language, France was the most commonly cited. But it’s the island’s English contingent that stands out most. Over 9% of islanders were born in England, compared to less than 4% in a typical Australian suburb. Around 16% of islanders have at least one parent born in England: the figure for the rest of Australia is closer to 6%. Almost half of islanders reported English ancestry, compared with one third of Australians as a whole. 84% of households on the island use only English at home, compared to 72% of households nationally.

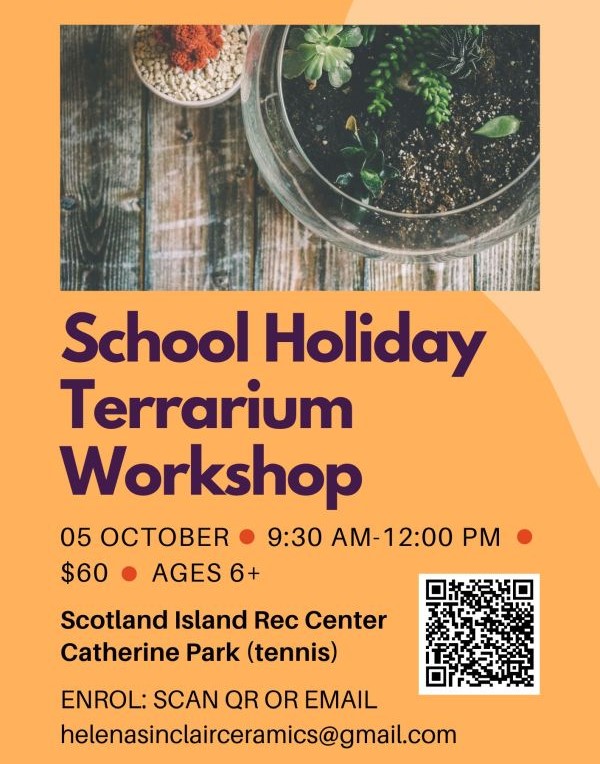

Returning to education, the most striking finding is that 43% of the island’s permanent adult population had a university degree, against 26% for Australia. This ties in with the fact that 53% of those in employment identified as ‘professionals’ or ‘managers’: the figure for Australia as a whole is 38%. In terms of median household income, the island was 37% ahead of the rest of Australia. 40% of households had an annual income above $156,000, compared with 24% across Australia. 85% of us owned our home, either outright (37%) or with a mortgage (48%). Australians in the rest of the country were more than twice as likely to rent but, unsurprisingly, they pay less. Many would say that living on Scotland Island is hard work, and the census figures possibly bear this out. 31% of islanders aged 15 or over report 15 or more hours per week of unpaid domestic work, which includes chores such as shopping and gardening. This compares with 21% of Australians as a whole. But some of us still find time to help others. 23% of islanders over 15 reported doing some kind of voluntary work through an organisation or group in the 12 months preceding the census, compared with 14% nationally. Putting all of this together, who typify Scotland Island’s permanent population? Taking ‘typical’ islanders to mean those with individual characteristics that reflect each of those most commonly found on our island, they are in their early 50s, married with children in primary school. They think of their ancestry as English, but were born in Australia to parents also born in this country. They are university-educated, ‘professional’, probably work in IT, and drive to a full-time job in order to pay off the mortgage on a three-bedroomed house. Not every islander fits that description. But then, few of us are exactly normal, are we? More details relating to the 2021 census of Scotland Island can be found here. School Holiday Terrarium WorkshopScotland Island Recreation CentreThursday, 5 October, 9.30 am - 12 noon For further

information or to enrol, click here.

'Secret Island': Second readingScotland Island Community HallSaturday, 7 October, 4 pm Following the success of The

Two Catherines, performed on Scotland Island in

June, Pittwater residents are embarking on another

theatrical venture: a new comedy written especially for

the offshore community. We are working towards

performances on Scotland Island in early March 2024.

Remember that, besides actors, we need lighting and sound operators, stage hands and many more. All are welcome to come along on Saturday. If you have questions about the play, send an email to editor@scotlandisland.org.au. The acting roles to fill are;

Elvina Bay Fireshed DinnerElvina Bay Fire StationSaturday, 7 October, 6 pm All proceeds go to support the work done by the volunteer members of the West Pittwater Rural Fire Brigade by improving safety, equipment and facilities. To help with catering, please RSVP and prepay via EFT by Thursday 5 October. Walk-ins cannot be guaranteed a meal. RSVP: firesheddinner@westpittwater.com.au EFT: West Pittwater Fire Brigade BSB: 032 196

Account: 960017

Ref: Add your surname as

reference

BYO. Fire Shed dinners are a volunteer community event.

Help with washing and packing up on the night would be

greatly appreciated.All fire brigade dinners are NO DOG events – please leave pets at home for the evening. The Tuesday Discussion GroupScotland Island Recreation CentreTuesday 17 October, 11 am - 12.30 pmThe Recreation Club runs a discussion group, meeting on the third Tuesday of each month, from 11 am to 12.30 pm in the Recreation Centre. Everyone is welcome. Members take it in turn to design a session. At the September session, CB Floyd led a discussion on the concept of 'meritocracy', and what they mean in practice.

For the October meeting, Roy Baker asks us 'what is intelligence?' Sometimes missing from the current brouhaha over artificial intelligence is clear agreement over what we mean by 'intelligence'. We use the term a lot, but how does it butt up against concepts such as intellect, knowledge, recall, understanding, empathy, morality, conciousness, self-awareness and so on? What's emotional or social intelligence? Are plants and other animal species intelligent? How do we best measure intelligence, develop it, use it and maintain it? And is AI as smart as it's cracked up to be? To prepare: 1. Read the Wikipedia article on intelligence, which offers at least ten different definitions of the word. (The listed references throw up additional reading suggestions). 2. Read this Conversation article on the topic

of human and AI hallucination. The group is administered

via a WhatsApp group, which will be used to distribute

further information about this and future discussions.

If you would like to be added to the group, send your

mobile phone number to editor@scotlandisland.org.au.

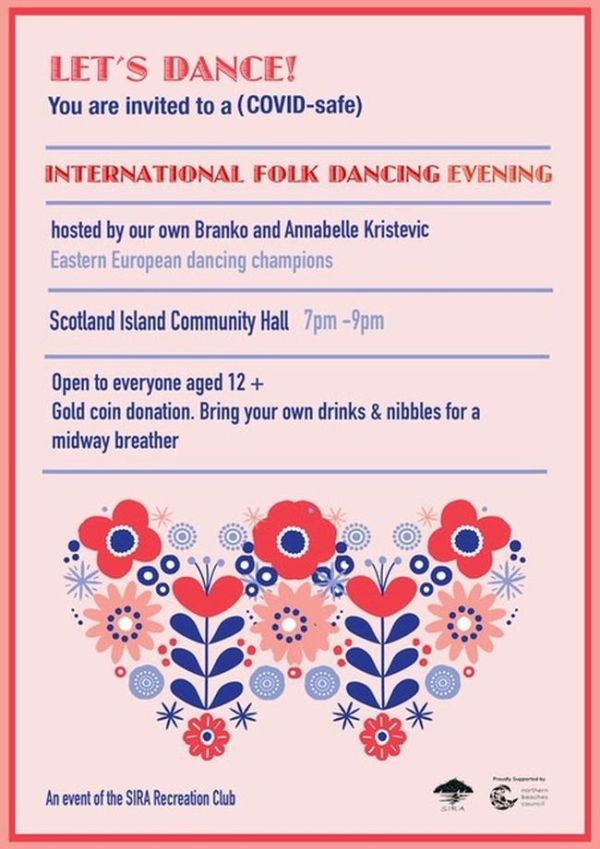

Alternatively, contact Jane Rich (janebalmain@hotmail.com) for more information or to express your interest in participating. The Recreation Club asks for $5 per person per attendance to defray expenses. Scotland Island CaféCatherine Park, Scotland IslandSunday 22 October, 10 am - 12 noon International Folk DancingScotland Island Community HallSaturday 28 October, 7 - 9 pm The Recreation

Club asks for $5 per person per attendance to

defray expenses.

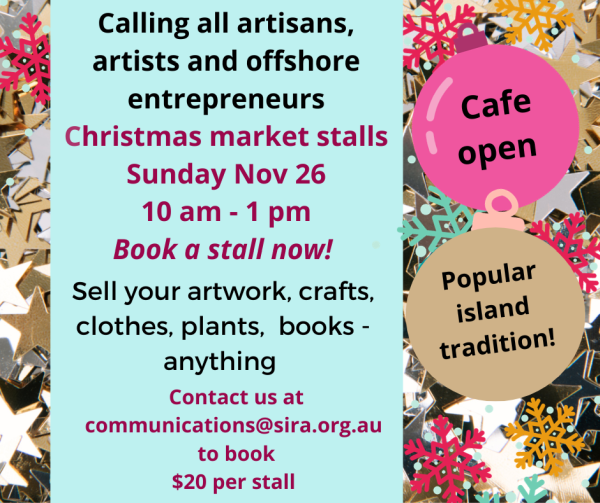

Christmas MarketScotland Island Catherine ParkSunday 26 November, 10 am - 1 pm Missed out on a previous newsletter? Past newsletters,

beginning May 2000, can be found at https://ymlp.com/archive_gesgjgm.php.

To ContributeIf you would like to contribute to this newsletter, please send an e-mail to the editor (editor@scotlandisland.org.au).Subscription InformationTo subscribe or unsubscribe, go to: http://www.scotlandisland.org.au/signup.

Scotland Island Community CalendarFor further information on island events, click hereThe Online Local Contacts GuideClick here to loadSIRA Photo Archive |

|||||||||||||||||

|