In this early summer Occasional, you'll hear about the Panther, burning water, tiny parking lots for chemicals, minipores and macropores. Find out where Mount PCB is located, what is turning the Yellow Sea green, and what caused the famous Cuyahoga River fires. Then there are the mystery of illegal molasses discharges in Jalisco and the sad loss of water in Magdalena. Water stories about Cleveland, Crater Lake, and Kalamazoo. More about the nitrate spike in Iowa, stream gauges in Idaho, the latest research on water and weight loss, and the world's fastest amphibious car. And, as always, there is much, much more.

The Pure Water Occasional is a weekly email magazine produced by Pure Water Products of Denton, Texas. We also publish the Pure Water Gazette, which puts up new articles about water and water treatment daily, providing “vast piles of information in the Gazette’s tangy, irreverent style” (USA Tomorrow). We also invite you to visit PureWaterProducts.com, the most information-rich commercial water treatment site on the worldwide web.

If you would like to read this issue on the Pure Water Gazette’s website, please go here.

While you were delivering your Fourth of July speech and worrying about the coup in Egypt and the fires in Arizona, a lot of interesting things happened in the ever-changing world of water. Read on to hear about some of them.

New from the Pure Water Gazette:

Cuyahoga River Fire

by Michael Rotman

Pure Water Gazette Introductory Note

When water catches fire it gets people's attention. We've all seen pictures recently of burning well water, laced with methane from hydraulic fracturing operations. So far, these spectacular displays have provoked only a timid "more studies are needed" response from environmental regulators. We may need a Cuyahoga River event to get the country's attention.

The Cuyahoga River at Cleveland caught fire at least 13 times in the past two centuries. The first recorded fire was in 1868. The "most fatal" was in 1912, when five people were killed. The final fire, 1969, although it wasn't the biggest or the worst of the Cuyahoga fires, played a big part in the advancement of the environmental reforms of the 1970s and was instrumental in the creation of the Clean Water Act. The 1969 fire came at a time when the country was ready to listen.

All the Cuyahoga fires (the 1952 fire was the worst) were the result of numerous petroleum spills, the dumping of fats and greases by slaugherhouses, acids from steel plants, and dyes from paint plants. There were also a lot of picnic benches, screen doors, automobile tires, boxes, and other combustible debris washed into the river by rains. Add to that much untreated human sewage from the Cleveland-Akron area, which may not have burned but certainly contributed to the stench.

Here is an account of the fires from a Cleveland historian. We've added the pictures and captions.--Hardly Waite.![]()

The story of the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969 - the event that sparked pop songs, lit the imagination of an entire nation, and badly tarnished a city's reputation - is built more on myths than reality. Yes, an oil slick on the Cuyahoga River - polluted from decades of industrial waste - caught fire on a Sunday morning in June 1969 near the Republic Steel mill, causing about $100,000 worth of damage to two railroad bridges. Initially the fire drew little attention, either locally or nationally. The '69 fire was not even the first time that the river burned. Dating back to the beginning of the twentieth century, the river had caught fire on several other occasions.

Photo of the 1948 Cuyahoga Fire. (Click picture for a larger view.)

The picture of the Cuyahoga River on fire that ended up in Time Magazine a month later - a truly arresting image showing flames leaping up from the water, completely engulfing a ship - was actually from a much more serious fire in November 1952. No picture of the '69 river fire is known to exist.

Throughout much of Cleveland's history, water pollution did not trouble the city's residents too much. Instead, water pollution was viewed as a necessary consequence of the industry that had brought the city prosperity. This attitude began to change in the 1960s as ideas associated with what would become known as environmentalism took shape. In 1968, Cleveland residents overwhelmingly passed a $100 million bond initiative to fund the Cuyahoga's clean up. Also, by this time deindustrialization was somewhat alleviating the pollution problem, as factories closed or cut back operations. Ironically, the city and its residents were beginning to take responsibility for the cleanliness of the river in the years before the infamous fire of 1969.

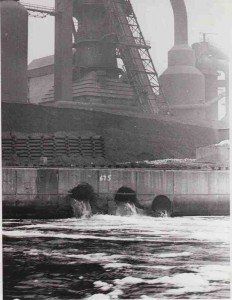

U.S. Steel plant belching untreated chemical discharge into the Cuyahoga in 1965. (Click picture for larger view.)

The '69 fire, then, was not really the terrifying climax of decades of pollution, but rather the last gasp of an industrial river whose role was beginning to change. Nevertheless, Cleveland became a symbol of environmental degradation. The Time article contributed to this, as did the notoriety of Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes. Stokes, who was the first black mayor of a major city when elected in 1968, became deeply involved with the issue, holding a press conference at the site of the fire the following day and testifying before Congress - including his brother US Representative Louis Stokes - to urge greater federal involvement in pollution control. The Stokes brothers' advocacy played a part in the passage of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972. In Cleveland, a number Cleveland State University students celebrated the inaugural Earth Day in 1970 by marching from campus to the river to protest pollution.

Cuyahoga on fire in 1952. This fire was the worst. (Click picture for a larger view.)

Even though it has been misunderstood, the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire did help bring about positive change. The river's water quality improved during the following decades, and business investors capitalized on this by converting parts of the Flats' abandoned industrial landscape into an entertainment district featuring restaurants, nightclubs, and music venues.

Much of the industry that both made Cleveland rich and caused its river to burn may never be coming back, but Clevelanders are meeting this challenge by reshaping their city to reflect its current realities.

The Cuyahoga Today Is Fireproof. Environmental Legislation Works.

Source: Clevelandhistorical.org

Micropores, Minipores, Molasses and Iodine

by Gene Franks

Filter carbon, the most basic ingredient of numerous water treatment devices, is a manufactured product. It is made from base materials like coal (bituminous, sub-bituminous, or lignite), coconut shells, wood, peat, fruit pits, nutshells and more.

Each of these substances has unique characteristics that make the resulting carbon perform uniquely. For example, lignite carbon and carbon made with  certain woods are best at removing colors like tannins from well water; coconut shell carbon is known for its ability to remove disinfection by-products and volatile organics; bituminous carbon gets the "best all-around" prize for doing almost everything pretty well.

certain woods are best at removing colors like tannins from well water; coconut shell carbon is known for its ability to remove disinfection by-products and volatile organics; bituminous carbon gets the "best all-around" prize for doing almost everything pretty well.

There is a reason why each carbon product is uniquely suited for specific jobs.![]()

The base material is prepared for use as filter carbon by a special activation process that involves high temperatures in a low-oxygen environment, followed by high pressure treatment with steam, carbon dioxide, or acids. The goal of activation is to produce a product with a complex pore structure that has a strong attractive power for organic molecules. It is the size and arrangement of the pore structure that makes each carbon uniquely suited for the reduction of specific contaminants.

Carbon makers have rating systems to measure their products' performance. These rating criteria are many: ash percentage, bulk density, abrasion number, and peroxide number, for example. In regard to pore size, which we are concerned with here, the main classifiers are the molasses number and the iodine number.

The molasses number measures carbon's large pores, know as macropores, which are officially defined as pores with a diameter of 0.01 microns (1,000 angstroms). The higher the concentration of macropores in the carbon, the higher the molasses number.

On the other hand, micropores, which have a diameter of less than 0.01 microns, are considered when assigning the carbon its iodine number. The iodine number expresses the milligrams of iodine than can be adsorbed by one gram of activated carbon. Iodine is a very small molecule and it takes carbon with small pores to adsorb it effectively.

Carbon with a high molasses number is best at adsorbing organic contaminants with a high molecular weight; a high iodine number indicates that the carbon will be good at removing contaminants with a very low molecular weight.

Water Filtration, a training and reference book published by the Water Quality Association, uses the analogy of a parking lot to explain how organic chemicals are adsorbed on filter carbon. I'm going to paraphrase:

The inside surface of the activated carbon particle can be viewed as a large parking lot for organic molecules. Further, one can view the large molecules as semitrucks, and the small organic molecules as compact cars. . . . If most of the pores in the activated carbon are micropores (small parking spaces), the semitrucks are going to have a difficult time moving inside the parking lot, and they will have difficulty finding a parking site which fits. But, the compact cars will have an easy time. [This parking lot has a high iodine number.] Second, if the pores are mostly macropores (large parking spaces), the semitrucks will be able to get around fine, but it will be an extremely inefficient way to park compact cars. [This lot has a high molasses number.] If there are only a few roads connecting the various areas inside the parking lot, the cars will all pile up, and the roads will act as a bottleneck. Ultimately, a large number of small cars can be parked, but the parking lot will fill slowly. This is what happens if there is not a suitable mix of micropores and macropores [as would be the case with a well balanced, bituminous carbon].

One final thing to note is that there are miles and miles of roads and lots of parking spaces in a relatively small amount of carbon. It is estimated that a teaspoon of activated carbon has a total surface area equal to a football field. That's why carbon is a prominent ingredient of almost all water treatment devices that aim at reduction of chemicals, disinfectants, colors, odors, and much more.

More New Articles. Please read these on the Gazette's website.

Hopes climb amid talks to clean contaminated ‘Mt. PCB’ in Kalamazoo

By Keith Matheny

This article gives a fine picture of the efforts of Kalamazoo citizens to get rid of “Mt. PCB,” a massive pile of toxic trash left behind when a wealthy corporation pocketed its profits and moved away. This story repeats itself again and again across the nation. Such toxic trash dumps are supposed to be cleaned up by the EPA “Superfund.” The Superfund was initially effective because it had money. Its funds came, logically and sensibly, from a corporate income tax and excise taxes on hazardous substances like petroleum and chemicals. When funding for the Superfund expired in 1995, Congress did not renew it. Instead, we now have a “plan” that funds cleanups like the Kalamazoo PCB mess by depending on the largesse of a stingy Congress and by attempting to collect the money from “primary responsible parties.” The “responsible parties” part usually produces more litigation than cleanup and leaves locals with the trash and the tab. In short, we’ve created another opportunity for corporate welfare where the rich reap the benefits and avoid the cleanup while taxpayers are stuck with the bill.–Hardly Waite.

China’s largest algal bloom turns the Yellow Sea green

by Karl Mathiesen

China’s Yellow Sea is turning green with massive growths of algae, which clog beaches and suffocate marine life. Industrial and agricultural discharges of nitrates and phosphates are the suspected cause.

The Politics of Water: Crater Lake National Park May Have to Truck in Drinking Water

Crater Lake National Park, which surrounds the deepest lake in the United States, may soon have insufficient water supplies for its public operations. State water regulations in the Klamath Basin have begun shutting off farmers’ and ranchers’ water for the first time — and could extend shutoffs to public lands including Crater Lake. The Klamath water controversy has been in the news for some time. This piece from the San Francisco Chronicle gives a good overview of the Klamath Basin situation.

Getting Methane out of Water

We hear a lot about methane in well water, especially as a side effect of the gas recovery process known as hydraulic fracturing. We hear a lot less about how to get rid of it. This article discusses water treatment for methane.

Other Water Stories You May Have Missed

Worst Water Article: Academia strikes again. Drink more water, lose more weight? After numerous studies examining numerous previous studies, academic researchers have concluded that water may help some dieters lose weight, but then again it may not.

Thousands of fish were asphyxiated at the Hurtado dam in Tlajomulco de Zúñiga in the Mexican state of Jalisco by a massive illegal discharge of molasses. Full story.

The world’s fastest amphibious car can change from car to boat in 15 seconds and reach 45 mph in water. It’s called the Panther and it is built in California. Full story.

The costs of rebuilding our nation’s water infrastructure are sobering. Estimates range from $300 billion to $1 trillion needed over the next 30 years. Who’s going to pay for this? American Rivers has a plan. Read the Full Report.

A state report has identified 290 New Mexico cities that are supplying water to residents from a single source. Relying on a single source is a risk for the communities served by these systems. If the spring or well dries up or becomes polluted, they have no backup supply. One village, Magdalena, recently lost all of its water when its well ran dry. Full Story.

The US Geological Survey operates some 7,000 stream gauges across the country, used by 850 other organizations for everything from watershed research to bridge design to water supply predictions and flood control. Each gauge costs around $14,000 to $18,000 to operate annually, and the budget cuts under sequestration have jeopardized about 375. Full Story.

The nitrate spike in the water of Iowa and particularly in the Des Moines area that the Occasional reported earlier is a “surprisingly long-lasting health threat that already has cost $500,000 in higher treatment costs and likely will lead to increased rates next year," according to Des Moines Water Works. Full Story.

The only thing better than a garden hose is a garden hose with a filter. Don’t be caught without a garden hose filter on National Garden Hose Day. It is less than a month until National Garden Hose Day. Full story.

Coming very soon to Pure Water Products: Sterilight UV.

Thank you for reading, and please stay tuned next Monday for another thrill-packed Occasional.

Places to Visit on Our Websites

Model 77: “The World’s Greatest $77 Water Filter”

”Sprite Shower Filters: You’ll Sing Better!”

An Alphabetical Index to Water Treatment Products

Write to the Gazette or the Occasional: pwp@purewaterproducts.com

Please Visit

The Pure Water Gazette – now in an easier to navigate format.

![occasionalbanner300[1]](https://ymlp.com/https.php?id=purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/occasionalbanner3001.gif)